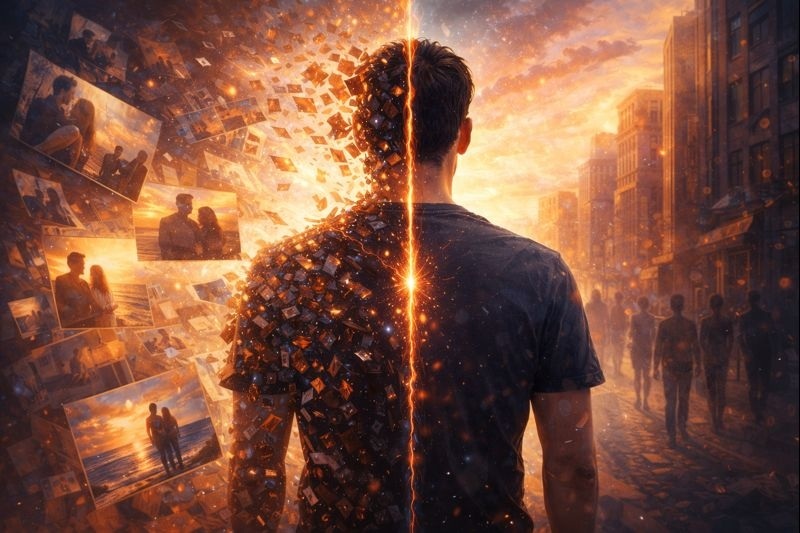

The tension between the remembered self vs lived self becomes noticeable when people realize that who they remember being no longer aligns with how they experience themselves in the present. This gap rarely appears suddenly. It forms quietly, shaped by memory, reinterpretation, and the way the mind continually edits the past to support the present moment.

What we live through and what we remember are not the same thing — and identity takes shape in the space between them.

Why the Remembered Self Slowly Replaces the Lived One

Experience happens once. Memory happens repeatedly.

Each time an event is recalled, it is reconstructed rather than retrieved. Emotional tone shifts. Details are emphasized, softened, or reframed. Meaning is adjusted to fit the current self-state. Over time, the remembered version of events becomes more familiar than the original lived experience.

The remembered self is not a distortion or a lie.

It is a compressed and edited version of reality.

Identity begins to organize itself around this version because it feels coherent, narratable, and easier to carry forward — both internally and socially. What is remembered becomes more influential than what was once directly felt.

Remembered Self vs Lived Self and the Construction of Identity

The contrast between the remembered self vs lived self reveals how identity is actually assembled. Identity does not form directly from experience, but from remembered experience.

The lived self exists only in the present moment.

The remembered self extends across time.

Because continuity depends on memory, identity gradually aligns with what is recalled rather than what was originally lived. This is why people may feel estranged from their past reactions or choices — not because they were unreal, but because they no longer fit the current narrative of the self.

Identity follows memory, not chronology.

How Emotional Weight Shapes What Gets Remembered

Not all experiences are remembered equally. Emotional intensity determines what is preserved, altered, or allowed to fade. Events associated with fear, shame, pride, or relief are more likely to be revisited internally, reinforcing their role in personal narrative.

Meanwhile, quieter experiences often disappear from memory, even if they once carried meaning.

This imbalance reshapes identity. The remembered self becomes disproportionately defined by emotionally charged moments, while the lived self was broader, more nuanced, and less dramatic. Over time, identity narrows around what memory repeatedly highlights.

When the Past Feels Like It Belongs to Someone Else

Many people describe a sense of distance from earlier versions of themselves. Memories remain accessible, yet emotionally detached — as if they belong to another person.

This does not indicate repression or denial.

It reflects a shift in identification.

As awareness evolves, the lived self no longer resonates with the emotional logic of past decisions. Memory remains intact, but identification loosens. What was once experienced as me becomes someone I remember being.

This separation can feel unsettling at first, but it also creates space for flexibility — allowing the self to respond rather than repeat.

This detachment often becomes visible after major life changes or trauma, when identity no longer feels continuous, even though memory remains intact.

Memory as a Narrative Tool, Not a Historical Record

Memory is designed for meaning, not accuracy. Its function is not to preserve the past as it was, but to help the self orient in the present.

By translating experience into narrative form, memory allows identity to remain coherent even as circumstances change. The cost of this coherence is distortion — not only of facts, but of emotional truth.

The remembered self offers continuity.

The lived self offers immediacy.

Confusing the two often leads to rigidity, where identity becomes governed by narrative rather than presence.

Memory functions less as an archive and more as an adaptive system that actively shapes identity, prioritizing coherence over accuracy.

Integrating the Gap Without Choosing One Over the Other

Integration does not require rejecting memory or abandoning narrative identity. It emerges when both the remembered and lived selves are recognized as processes rather than authorities.

As attention shifts toward present-moment awareness, the lived self becomes visible again. Memory remains available, but no longer dictates identity automatically. The self regains adaptability without losing coherence.

This shift often mirrors broader changes in how reality itself is experienced, especially after moments that disrupt perceived continuity.

Identity becomes something experienced, not defended.

Final Reflection

The tension between the remembered self vs lived self is not a flaw in human cognition. It is a feature that allows identity to survive change.

Difficulty arises only when memory is mistaken for reality, or when narrative replaces presence. Recognizing the difference does not fragment the self — it releases identity from being governed solely by memory.

In that release, the self becomes more flexible, more responsive, and more aligned with what is actually being lived.